The Alphabet Shift in Kazakh Language

Over years of research and work in Kazakhstan, I have seen many Latin representations of the Kazakh alphabet. Some were pockmarked with apostrophes – others riddled with diacritics. Others still imposed Latin letters incorrectly on the Russian language, creating the following image (from the mobile application of www.soyle.kz, a state-sponsored site that offers free Kazakh language lessons):

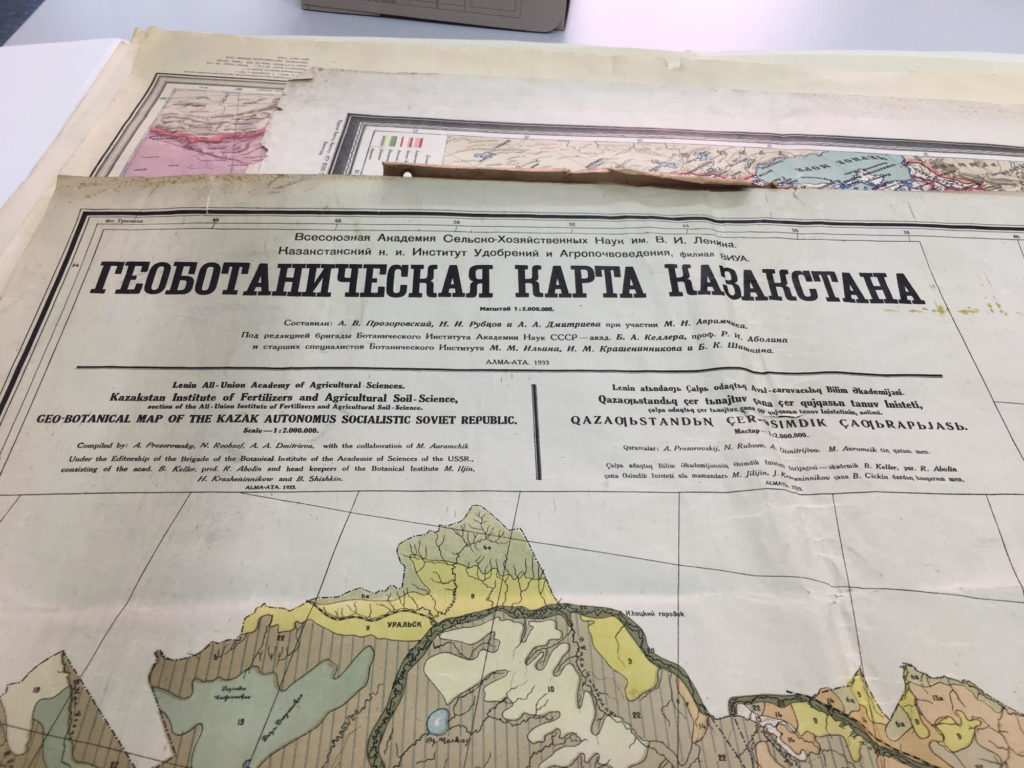

Over the past century alone, Kazakhstan has switched alphabets three times (Arabic, Latin, and Cyrillic, respectively) – with a fourth on the horizon. Unsurprisingly, the decision to switch alphabets yet again met with a variety of reactions, both domestically and internationally. Kazakhstani newspapers have generally upheld the shift as a move toward modernization, while many Russian ones have reacted negatively. Indeed, the Russian media has relied prominently on Soviet-era tropes of “culture” and “cultured-ness” (kul’tura and kul’turnost’, respectively) in its coverage of the Kazakh alphabet shift, illuminating its reliance on a deeply Soviet worldview – and its belief that Kazakhstan is leaving it behind.

History of Alphabet Shift and Language in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan is among the most Russified former Soviet republics – and even today, Russian remains the primary language of government, science, and business despite state efforts to promote linguistic “Kazakhization”. This prevalence of the Russian language in Kazakhstan is integrally related to the continued presence of the Kazakh Cyrillic alphabet: in the Soviet era, the Russian language was a symbol of modernization, as was its associated alphabet, Cyrillic. In that vein, former president Nazarbayev has claimed that the switch to Latin is also part of Kazakhstan’s modernization process, which could be perceived as part of being “cultured.”

The Soviet idea of “culture” has deep roots. Scholar Svetlana Boym writes that “in the nineteenth century culture is often synonymous with literature, and Russians are defined less by blood and by class than by being a unique community of readers of Russian literature.” In the Soviet context, however, “culture” extended beyond this 19th-century conception of literature to include the qualities of the individual who had read these books: in the 1920s, discussions of “cultural revolution” “became the advocacy of kul’turnost’, which “include[d] not only the new Soviet artistic canon but also manners, ways of behavior, and discerning taste in consumer goods. Culturalization is a way of translating ideology into the everyday.” Such ideology, naturally, had to be adapted to the individual republics. In the case of Kazakhstan – previously a largely oral culture – creating “national culture” (“artistic canon,” in Boym’s words) meant, among other things, creating a canon of Kazakh national literature that reflected history and tradition while simultaneously espousing Soviet ideology.

Iurii Bogdanov’s article in Izvestiia, largely concerns itself, rather, with the logistical issues of Kazakhstan’s alphabet shift – but he is nevertheless sure to mention “[the shift’s] negative impact on the development of the humanities, as well as the possibility of access to literary and scientific heritage.” This is clearest in a quote from Bulat Sultanov, the director of the Institute for International and Regional Cooperation at the Kazakh-German University: Bogdanov cites him, in a short albeit separate paragraph, as saying that “during the Soviet years, a solid mass of literature was formed in Kazakhstan – and it was all translated and published in Cyrillic. All of this will be lost for future generations.”

Although Sultanov does not explicitly credit the USSR with creating modern Kazakh literary culture, he admits that a period of great literary creativity and formation of literary heritage (also viewed as “national culture”) took place during the Soviet era – when it was largely produced in Cyrillic. He does not, for example, refer to the period when Baitursynuly’s reformed Arabic alphabet was used to print Kazakh texts or the pre-Soviet period during which many Kazakh stories, legends, and songs were orally preserved. Sultanov’s – and thus, Bogdanov’s – emphasis is specifically on the creation of a printed body of national Kazakh literature in Cyrillic which bears the positive Soviet legacy of the Russian language. For Sultanov and Bogdanov, however, the new Latin script destroys the accessibility (and thus relevance) of the Soviet-created literary canon for future generations of Kazakhs, who would now be unable to engage in their “national culture.”

Nikita Mendikovich writes more caustically about the impact of the alphabet shift on Kazakh “national culture” on Lenta.ru. The article opens by claiming that “yet another attack on the Russian language and Cyrillic is unfolding in Kazakhstan,” reinforcing the relationship between the Russian language and Cyrillic alphabet. Mendikovich quotes Askhat Aimagambetov, the Minister of Education, as saying that “education in the state language [Kazakh] should be dominant,” followed by a timeline of the alphabet shift. Mendikovich makes it clear that Kazakhstan’s “national culture” will be corrupted by this alphabet and attendant language shift: “in reality, Minister Aimagamembetov’s motives in speaking out for the Kazakhization of schools… have little to do with concern for the national language or national culture.” Indeed, Mendikovich states that Kazakhstan’s level of “national culture” will drop following Latinization, as he claims that the overwhelming majority of Kazakhstani media – especially books – is in Russian. With that, Mendikovich claims that “the Kazakh language has practically stopped being used in literary or academic texts”: for him, Russian is the superior “language of culture,” given its dominance in the sphere of the printed word – and Cyrillic must reign within it. According to Mendikovich, the “secondary status” of the Kazakh language precludes it from attaining the Russian language’s prestige – meaning that the Cyrillic alphabet, too, will remain culturally superior as long as Russian remains dominant in Kazakhstan’s literary and media sphere. Even after Latinization.

Mendikovich also quotes Kazakhstani philologist Dastan El’desov as saying that “instead of the language of Abay and Auezov, we have the language of newspaper journalism [publitsistika] and social media, in which it is very hard to write texts on philosophical, legal, academic, and other subjects.” In that one sentence, Mendikovich juxtaposes two versions of the Kazakh language: “the language of Abay and Auezov,” both of whom were included in the Soviet Kazakh literary “culture,” and the “language of newspaper journalism and social media,” which were not. The “language of Abay and Auezov” is rendered in Cyrillic, given that their writings were largely canonized in the Soviet period, while the “language of newspaper journalism and social media” is increasingly rendered in Latin – online. The former is considered “cultured,” as it represents the peak of Kazakh literary culture; the latter is not, as it cannot discuss “philosophical, legal, academic, and other subjects,” which was the content of the Soviet-era, Cyrillic, Kazakh literary world. Mendikovich laments the degradation of a language and alphabet that, in his view, represented the peak of Kazakh literature and, consequently, culture.

It may appear strange that Russia – a sovereign nation – concerns itself with the loss of culture in Kazakhstan, another sovereign nation. Yet Kazakhstan has been not only aligned with Russia, but also been under its control (whether in the USSR or the CIS) for the whole century – and is now changing one of its most visible outward symbols of adherence to the Russian space and Soviet legacy. Consequently, the Russian media relies on tropes that extol the “gifts” of the Soviet era to Kazakhstan, i.e., culture: a worldview rooted in conceptions of the Soviet past to which Kazakhstan is expected to conform some thirty years after independence. The Russian media analyzed here posits that Kazakhstan is leaving its Soviet past behind, even if doing so entails a risk to its “culture,” its literature, and its art.

by Leora Eisenberg